SAE KIM

curated patterns of thoughts and behavior

RETHINKING MANHATTAN'S GRID: Research & Analysis

OVERVIEW

In many cities, grid has performed as a framework that provides both a guideline, in which the urban could expand its territories indefinitely, and a platform, in which the city could grow systematically. The simplicity and abstractness embedded in the grid -- coincided with social, economical, political, and geographical factors -- has enabled multiple interpretations and variances to occur, inevitably pushing different cities to have a unique urban form. Manhattan is a paramount model of a gridded city that exemplifies how the grid can function to measure certain energies of the city and translate them to suggest larger urban ideas.

The grid of Manhattan -- while maintaining its original character of the grid conceptualized in the Commissioner's Plan of 1811 -- has gone through very specific types of transformation that respond to various dynamics in the city and such transformations have accumulated over two centuries to build up hierarchies in different urban systems that relate to economy, infrastructure, ethnicity, zoning, and many others. These transformative energies provided opportunities for the grid to respond in various ways.

The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 of Manhattan began to be implemented in the nineteenth century when a uniform, continuous grid was masterminded as a single project responding to the city’s need for growth.

Manhattan had the ambition to not only provide room for demographic expansion but to grow economically as well. The scope of Manhattan’s growth, at this point, was already headed towards the global market, targeting European and Asian cities that already had over one million inhabitants. In 1807, the state legislature asked three commissioners -- Morris, De Witt, and Rutherfurd -- to generate a plan “most conducive to the public good.” After four years, the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811 came about, signed by various authorities, to be implemented in the island of Manhattan.

The Commissioner’s Plan of 1811 had all the support from the government. When the plan was first submitted to the officials, vast chunk of island was already parceled into private owners. Although the parcel division was not systematic, invading an individual’s rights would be going against the foundational rules set at the time of independence of America. Incredible amount of political and legal reinforcement was required through rigorous process of negotiating and compromising with the private landowners. But ultimately, as the initial conception of the plan came about due to the request from the state legislature, the Commissioner’s Plan became “the first large-scale act of eminent domain in the city’s history.”

Although the political and economical intentions behind the Commissioner’s Plan was extremely ambitious, the extent of morphologic detail in which the plan defined was rather unambitious or unspecific. A simple line drawing, the 1811 plan is not pictorial in effect; yet it is a potent image, conveying the illusion of the island as a blank slate. The plan has little graphic detailing: virtually no shading, contour lines, or indication of relief, and no signs of population density; the 1811 plan was a diagram. But perhaps this diagrammatic character of the plan was the most successful part about the 1811 plan: that instead of articulating a sense of a place, it records an ordering system.

The current condition of Manhattan strongly resemble much of what was originally planned although alterations and changes made over two decades are apparent. And in the context of exploring the potentials of grid’s logical framework and conveying the dyadic and bivalent characteristic of an abstract grid, the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811 provides wide range of development patterns.

The grid of Manhattan -- while maintaining its original character for two centuries -- has gone through very specific types of transformation that respond to various dynamics in the city. The projects that have fostered these transformations to happen have accumulated over two hundred years to build up hierarchies in different urban systems that relate to economy, infrastructure, ethnicity, zoning, and many others: innate character of these urban projects depict much more than just the design values.

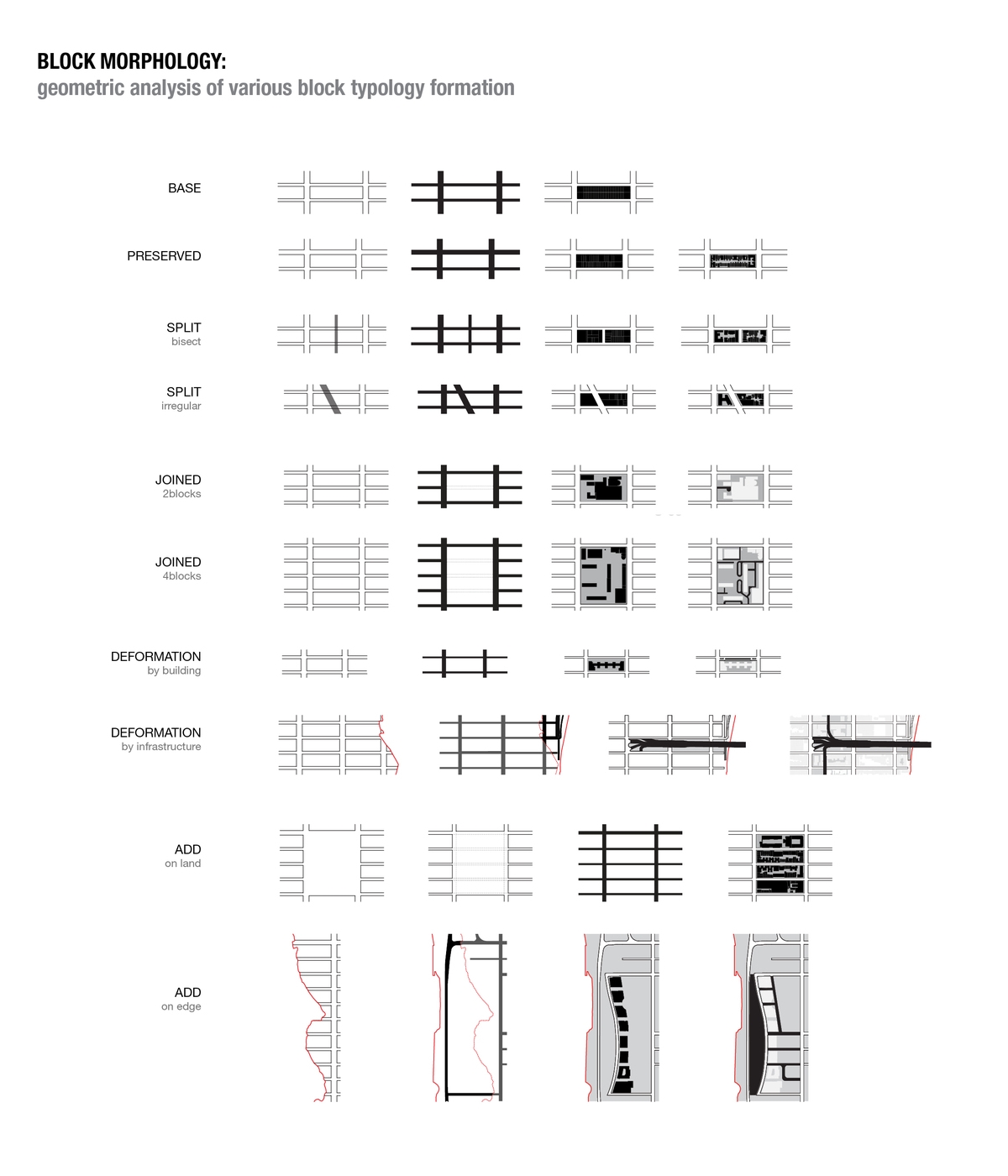

Development patterns within Manhattan's grid did not put much emphasis in trying to adhere to the Commissioner's Plan of 1811. One reason was because the plan of 1811 excluded morphological agenda other than the block size; another reason was because the primary agenda of Manhattan was in the economic development. Many projects within Manhattan reflected the phenomenon of how the rules of the grid began to give in to the economic energies of the city. The Lincoln Center, for example, merged three urban blocks into one to create a cultural hub for performance arts. While it is questionable how many people would actually visit more than one theater on a single visit, new scale of merged blocks effectively makes Lincoln Center’s presence known while retaining to the system of Manhattan's grid. The Grand Central Terminal, like the Lincoln Center, also generates a maxi-grid. However the Grand Central Terminal -- atop of covering three urban blocks at 42nd street -- is the only building in New York to obstruct a grid avenue and force a detour around itself.

Concentration of these types of buildings, primarily associated with infrastructural network or main entertainment venues, can be found in midtown area where bias of city's economic activity contrasts to the uniform character inherent in the grid. In these blocks, the rules of the grid no longer functions as a framework but rather a limitation. The grid therefore transforms to accommodate for the overflowing urban energy that it can no longer contain.

The urban development patterns of Manhattan saw the infinite grid as fitting for accommodating growth. Yet it is evident that there were multiple factors that came into play in the last two hundred years to convey multiple ways in which the grid -- as an urban framework -- can be translated. Coincided with these differences were historical events and urban projects of different types and scales that ultimately produced ripples of urban behaviors to be overlayed on top of the grid system.

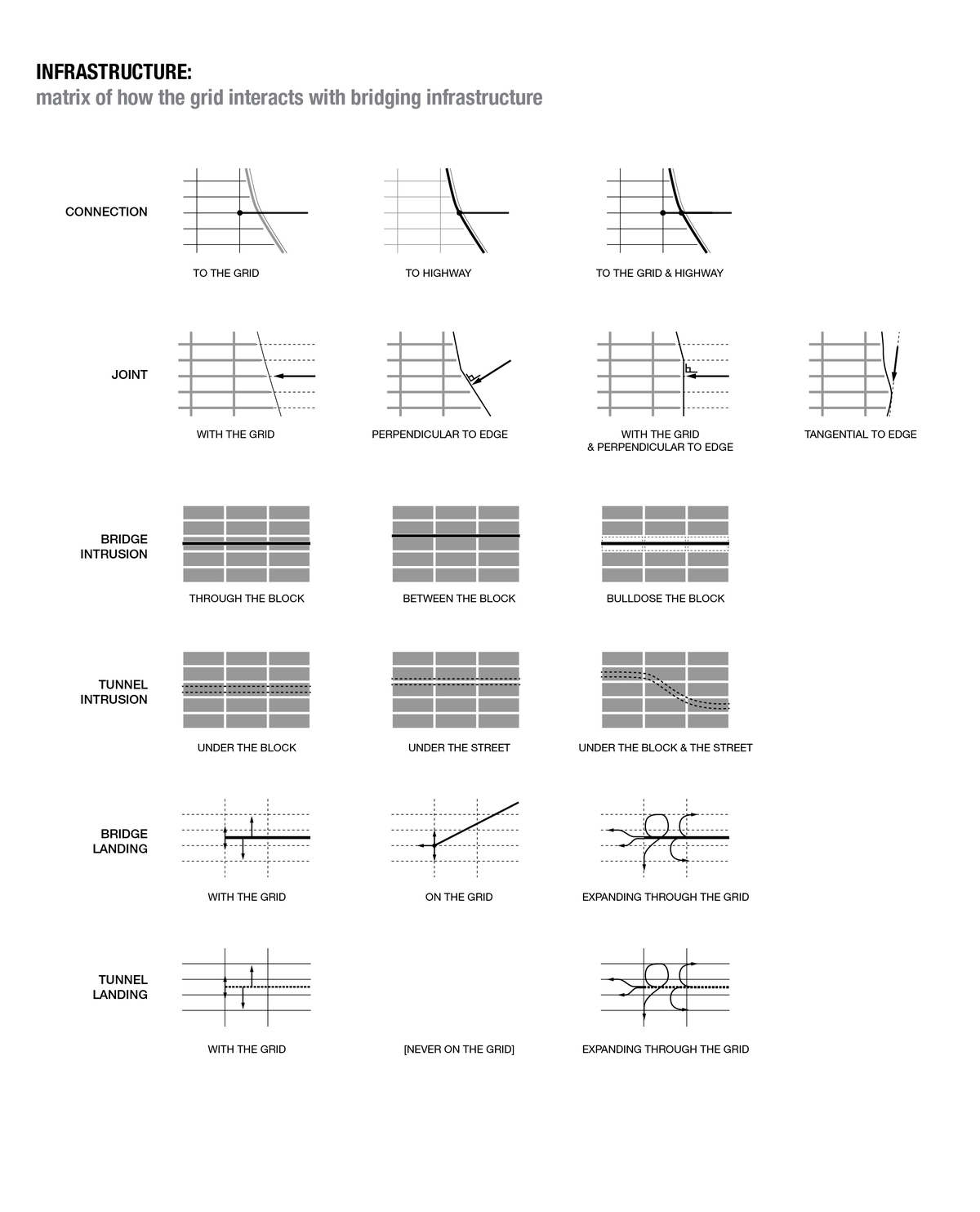

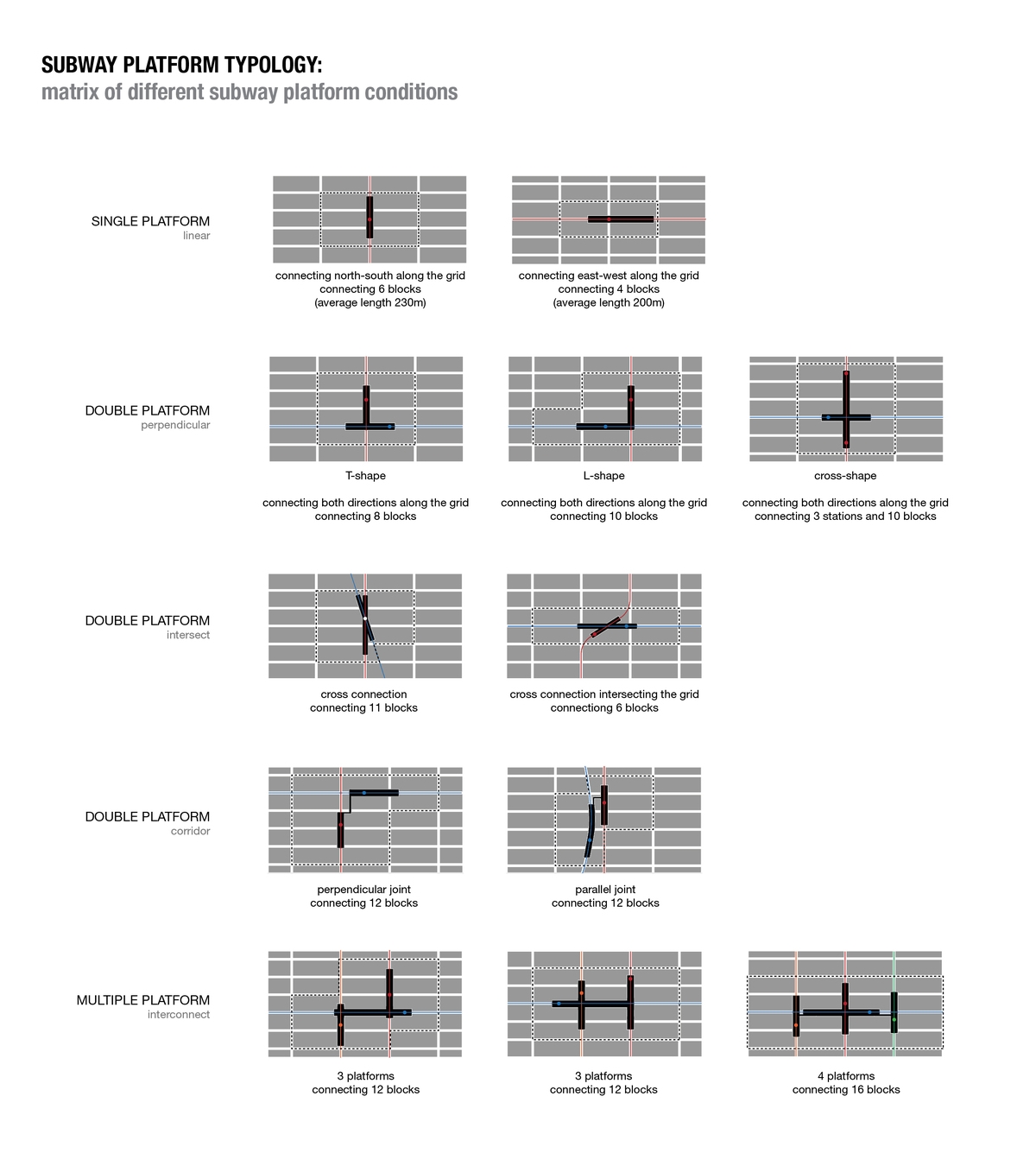

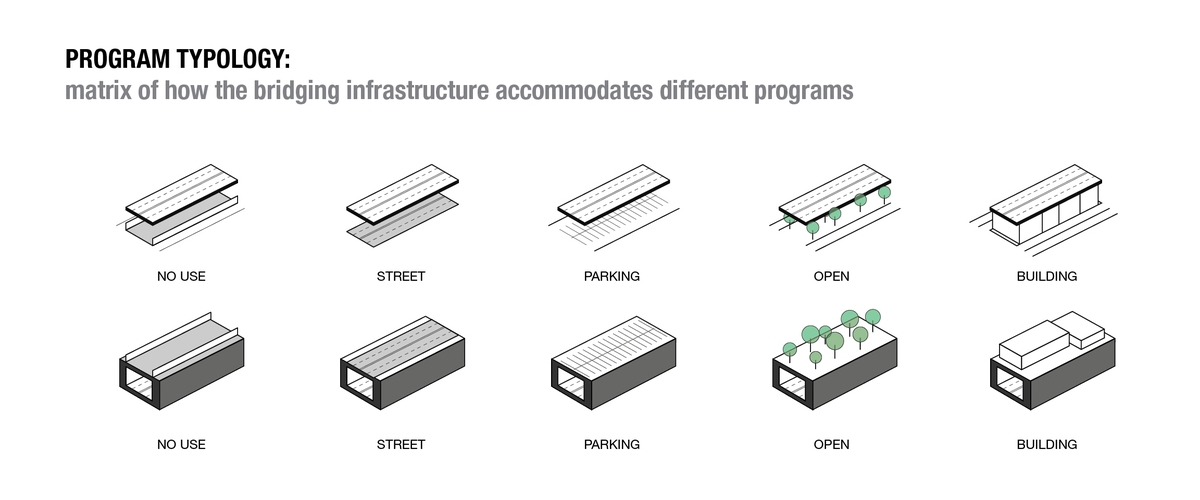

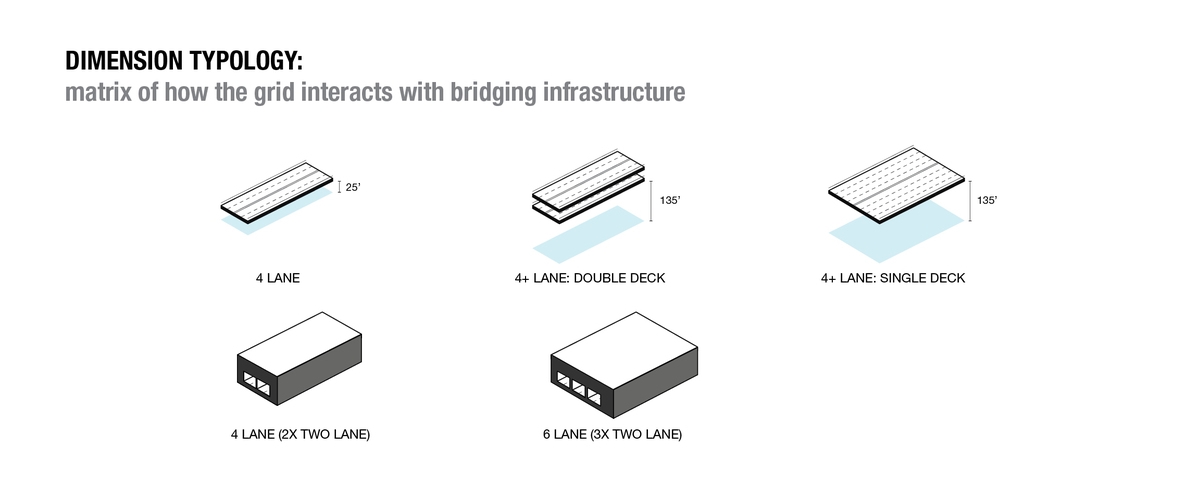

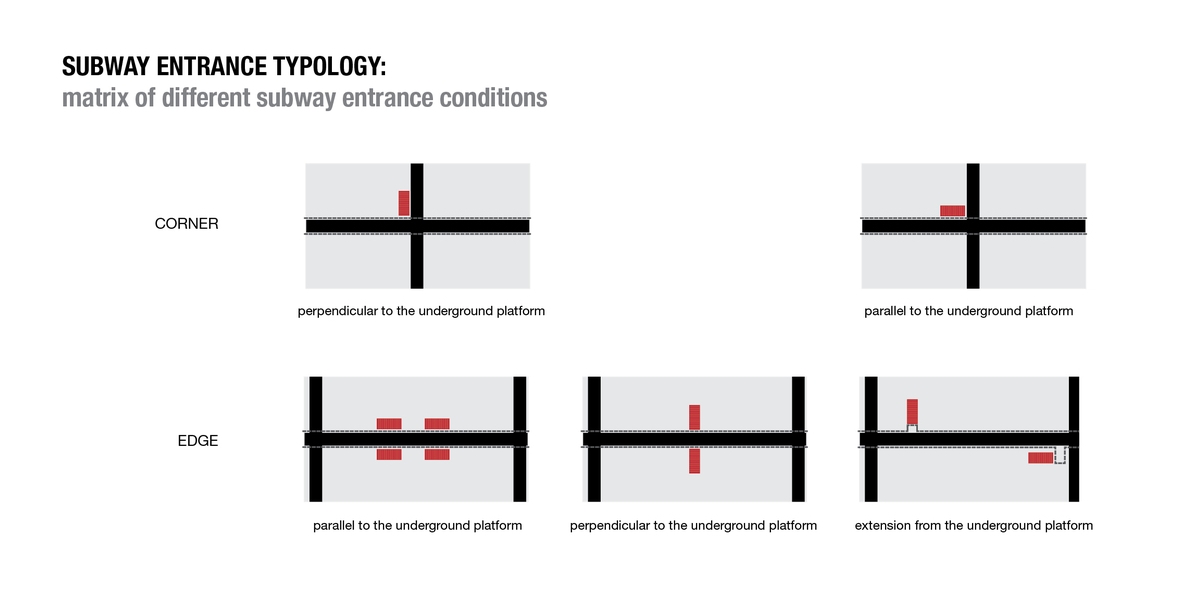

Taking into assumption that there exists identifiable patterns in the way a city is developed, the Commissioners’ Plan is juxtaposed with the current configuration of Manhattan to reveal the formal logic embedded in the physical elements of Manhattan. Not only is the island diagnosed at the scale of the whole, it is also scanned at the scale of a block and building. Various block morphologies as well as different infrastructural typologies are identified, analyzed, and categorized as a means of projecting the possibility of the grid in the urban form of Manhattan.

ISSUE 1: Unidirectional Infrastructure

The original settlement of Manhattan in the eighteenth century happened at the southern tip of the island. Although the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 outlined how the rest of the island should be developed, such ambitious plan did not happen overnight. Undeveloped lands began to be parceled and occupied according to the Commissioners’ Plan and already-settled lands began to further develop, accommodating taller, larger, and more significant buildings.

Because of the island’s North-South orientation and its original settlement location, the city could only grow to the north. All the necessary infrastructure are displaced in the long direction as a means of servicing the whole island. Most of main traffic arteries, highways, subway lines, and railroads emphasize the North-South direction. Such gestures -- while facilitating ease of movement in the long direction -- cause inconvenience for East-West movement.

Street and block dimensions also reflect dominance of North-South axis. Because the width of a Manhattan block is typically two to three times longer than its length, the movement in the East-West direction is seemingly less frequent than the North-South direction. Furthermore, traffic flow along the streets are much more ‘obstructed’ than that along the avenues.

ISSUE 2: Unspecific Neighborhood

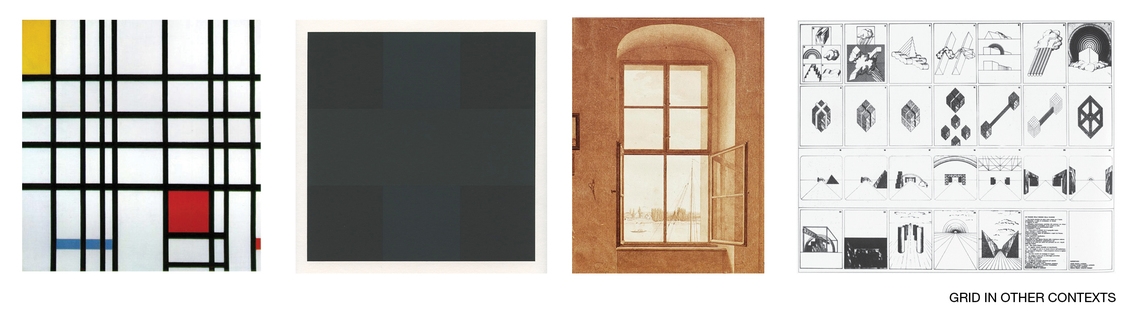

The ways in which a sense of space, time, hierarchy, and change is absent in the generic grid ironically provide the very potential for it to be all of the above. The grid, therefore, is both connotative and denotative; it is both centrifugal and centripetal; it is both beyond-the-frame and within-the-frame. This innate characteristics of the grid justify all the reason why the same grid has always successfully provided a unique framework for cities.

But how would one orient herself in the city if the streets and avenues did not have green numbered signs on every corner? Surely, key buildings and landmarks would play a role. But the symmetric nature of the urban block and parcel layout based on a generic grid have promoted developments that are uniform in character. Although this notion of evenness and anti-directionality have expedited Manhattan to expand and develop successfully in relatively short period, it has nonetheless produced an urban form that could be copied and pasted infinitely. Different neighbors and districts display only subtle and nuanced variation of urban experience and these minor differences are not even intentional.